Mandible

| Bone: Mandible | |

|---|---|

|

|

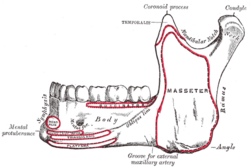

| Mandible. Outer surface. Side view | |

|

|

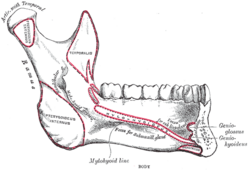

| Mandible. Inner surface. Side view | |

| Latin | mandibula |

| Gray's | subject #44 172 |

| Precursor | 1st branchial arch[1] |

| MeSH | Mandible |

The mandible (from Latin mandibula, "jawbone") or inferior maxillary bone forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The term "mandible" also refers to both the upper and lower sections of the beaks of birds; in this case the "lower mandible" corresponds to the mandible of humans, while the "upper mandible" is functionally equivalent to the human maxilla but mainly consists of the premaxillary bones. Conversely, in bony fish for example, the lower jaw may be termed "lower maxilla".

Contents |

Components

The mandible consists of:

- a curved, horizontal portion, the body. (See body of mandible).

- two perpendicular portions, the rami, which unite with the ends of the body nearly at right angles. (See ramus mandibulae)

- Alveolar process, the tooth bearing area of the mandible (upper part of the body of the mandible)

- Condyle, superior (upper) and posterior projection from the ramus, which makes the temporomandibular joint with the temporal bone

- Coronoid process, superior and anterior projection from the ramus. This provides attachment to the temporalis muscle

Foramina (singular=foramen)

- Mandibular foramen, paired, in the inner (medial) aspect of the mandible, superior to the mandibular angle in the middle of the ramus.

- Mental foramen, paired, lateral to the mental protuberance on the body of mandible.

Nerves

Inferior alveolar nerve, branch of the mandibular division of Trigeminal (V) nerve, enters the mandibular foramen and runs forward in the mandibular canal, supplying sensation to the teeth. At the mental foramen the nerve divides into two terminal branches: incisive and mental nerves. The incisive nerve runs forward in the mandible and supplies the anterior teeth. The mental nerve exits the mental foramen and supplies sensation to the lower lip.

Articulations

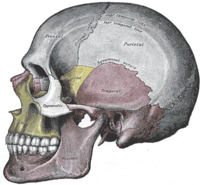

The mandible articulates with the two temporal bones at the temporomandibular joints.

Pathologies

One fifth of facial injuries involve mandibular fracture.[2] Mandibular fractures are often accompanied by a 'twin fracture' on the contralateral (opposite) side.

Aetiology

- Motor vehicle accident (MVA) - 40%

- Assault - 40%

- Fall - 10%

- Sport - 5%

- Other - 5%

Location

- Condyle - 30%

- Angle - 25%

- Body - 25%

- Symphesis - 15%

- Ramus - 3%

- Coronoid process - 2%

The mandible may be dislocated anteriorly (to the front) and inferiorly (downwards) but very rarely posteriorly (backwards).

In other vertebrates

In lobe-finned fishes and the early fossil tetrapods, the bone homologous to the mandible of mammals is merely the largest of several bones in the lower jaw. In such animals, it is referred to as the dentary bone, and forms the body of the outer surface of the jaw. It is bordered below by a number of splenial bones, while the angle of the jaw is formed by a lower angular bone and a suprangular bone just above it. The inner surface of the jaw is lined by a prearticular bone, while the articular bone forms the articulation with the skull proper. Finally a set of three narrow coronoid bones lie above the prearticular bone. As the name implies, the majority of the teeth are attached to the dentary, but there are commonly also teeth on the coronoid bones, and sometimes on the prearticular as well.[3]

This complex primitive pattern has, however, been simplified to various degrees in the great majority of vertebrates, as bones have either fused or vanished entirely. In teleosts, only the dentary, articular, and angular bones remain, while in living amphibians, the dentary is accompanied only by the prearticular, and, in salamanders, one of the coronoids. The lower jaw of reptiles has only a single coronoid and splenial, but retains all the other primitive bones except the prearticular.[3]

While, in birds, these various bones have fused into a single structure, in mammals most of them have disappeared, leaving an enlarged dentary as the only remaining bone in the lower jaw - the mandible. As a result of this, the primitive jaw articulation, between the articular and quadrate bones, has been lost, and replaced with an entirely new articulation between the mandible and the temporal bone. An intermediate stage can be seen in some therapsids, in which both points of articulation are present. Aside from the dentary, only few other bones of the primitive lower jaw remain in mammals; the former articular and quadrate bones survive as the malleus and the incus of the middle ear.[3]

Finally, the cartilagenous fish, such as sharks, do not have any of the bones found in the lower jaw of other vertebrates. Instead, their lower jaw is composed of a cartilagenous structure homologous with the Meckel's cartilage of other groups. This also remains a significant element of the jaw in some primitive bony fish, such as sturgeons.[3]

See also

- Bone terminology

- Terms for anatomical location

- Changes produced in the mandible by age

- Ossification of the mandible

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Simian shelf

Additional images

Front |

Mandible |

Gray181.png |

Facial bones |

Side view of the skull. |

The skull from the front. |

The veins of the neck, viewed from in front. |

References

- ↑ hednk-023 — Embryology at UNC

- ↑ Levin L, Zadik Y, Peleg K, Bigman G, Givon A, Lin S (August 2008). "Incidence and severity of maxillofacial injuries during the Second Lebanon War among Israeli soldiers and civilians". J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66 (8): 1630–3. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2007.11.028. PMID 18634951. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WKF-4T0F864-K&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=e05fa24fcd1ba3f710eea659d919b6eb. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 244–247. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

- SUNY Labs 34:st-0203 – "Oral Cavity: Bones"

- Diagram at uni-mainz.de

This article was originally based on an entry from a public domain edition of Gray's Anatomy. As such, some of the information contained within it may be outdated.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||